My favorite thing about programming is the fact that you never run out of opportunities to be completely floored. There’s literally always either a concept, theory, framework, or language that you don’t know. This is actually fantastic, because there’s no dearth of opportunity when it comes to learning. And you always come head-to-head with these facts when you pair program with a more experienced developer.

One of the new concepts that I encountered this week was the idea of state machines, sometimes referred to as “finite state machines”. At first I thought that this was something unique to the gem that we are using in one of our large-scale applications, but it turns out it’s not a Rails thing. In fact, it’s not even a Ruby thing! It’s a Computer Science thing; to be a bit more specific, it’s a mathematical abstraction used to design complex algorithms. But for all intents and purposes, it’s a Computer Science theory that we use almost all the time, whether we know it or not.

If you got through that paragraph without freaking out, you deserve a medal. All this CS theory sounds terrifying, right? Well, don’t worry. For programming purposes, you don’t actually need to think too much about how state machines are constructed and what’s being abstracted away. Even though state machines can get incredibly complex, relatively quickly, let’s not overwhelm ourselves; we only need to think about state machines in the context of programming. So we’ll keep it simple and focus on what state machines are, how they work, and when to use them.

State Machines: What Are They?

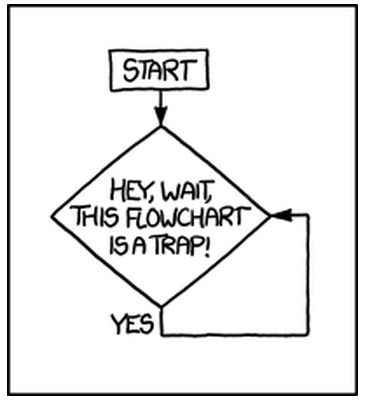

A state machine is nothing more than a flow chart. And here’s the thing about flowcharts: they’re everywhere. If you think about it, a flowchart is just a way of controlling the flow of a set of actions. You have different conditions, and depending on your condition – or “state”, as we refer to it in programmatic terms – you’ll take a certain action.

For example, if you’re hungry, you’ll eat some food, probably a slice of cheesecake. If you’re still hungry, you’ll eat another slice. When you’re full, you’ll stop eating cheesecake (LOL, like anyone could ever be “too full” from cheesecake). You have different states of being, and certain events trigger you to move from one state to another – from hungry, to less hungry, to completely full.

One of the simplest definitions that I found for state machines in the context of programming comes from a Lamson Project blog post :

A practical finite state machine is basically four things: 1) A bunch of functions, or things that need to get done. 2) A bunch of events, or reasons to call these functions. 3) Some piece of data that tracks the “state” this bunch of functions is in. 4) Code inside the functions that says how to “transition” or “change” into the next state for further processing.

At the risk of sounding a bit philosophical, it all boils down to actions that are taken, and the reasons we take certain actions. State machines are how we keep track of different events, and control the flow between those events.

A State Of Being: How to Use State Machines

The best way of understanding how to use a state machine in your own application is by seeing an example of it in another application. A good place to start is usually a commonly-used, large-scale web application. Since we’ve been using my bookstore application in prior blog posts, we’ll use another eCommerce example to understand state machines. Here’s a very simplified example of a basic order processing state machine:

If we follow the event flow, we start to get an idea of the different actions that trigger different states. Each Order starts off with an initial state (something that we’ll explore a bit more when we build our own state machine), and requires a certain event to occur for its state to change. This means that only if an Order is placed, will the Order’s state be changed to submitted.

The event triggers are important because without them, there wouldn’t be enough clarity to move from one state to another. Take a look at the Order when it’s in the processing state. The Order must be either fulfilled or canceled in order for it to proceed to the next state.

This particular state machine is very simple, and doesn’t even account for the return or refund process! Imagine what that might look like! You could have states that could have events that refer back to themselves, which would make them directed acyclic graphs. Things would start to get really complicated, really fast.

But, if we think back to the Lamson Project’s definition of a state machine, our order processing example still fits the bill:

- Our functions, the stuff that needs to get done, are the different things that need to happen for an event to trigger. For example, the

Userhas to input a valid credit card number, cvv, expiration date, and shipping address just so that theOrdercan transition fromunplacedtosubmitted. - Our events, the reasons to call the functions, are the actual actions taken during the flow of the machine. The

Useractually has to successfully submit the form and the data has to be passed from theUserand stored in the database so that the event can successfully occur. - Our states, the data that tracks these functions, are the different conditions that our order can be in. If the

Orderisprocessing, all the functionality of fulfilling, packaging, and shipping the order must all be contained within that state. - Our code inside the functions would be all the intricate methods that do all the work prior to each event occurring and each state changing. For example, you’d probably have a validation to check whether the user had input a valid zip code (something like

validates :zip_code_length) before transitioning from anunplacedOrderto asubmittedone. And you’d probably want to execute anin_stock?method before switching from theprocessingstate to theshippedstate.

The Case For State Machines

While understanding state machines is great, is it always the right tool for the job? From my research and reading, it seems like most of the time, it is. This post by Alan Skorkin gives some pretty good insight into why developers never use state machines. Many developers seem to be intimidated by the very concept of state machines, or sometimes don’t even understand them in the first place, which can be cause to avoid them at all costs. Other programmers see them as complex and overly complicated, and perhaps not necessary when you’re first starting off in building your application. And sometimes it’s just hard to foresee how your application is going to grow, and determine whether or not a state machine is the right tool for the job.

Even though setting up a state machine takes a bit of initial effort, it can save you a lot of pain in the long run. Even though many programmers can’t predict when they’ll need a state machine, almost every application has some form of flow that fits the bill. And let’s face it: almost every web application these days actually strives to do something, which means that it will inevitably have some sort of flow of events.

This fantastic Shopify blog post makes a great case for why ever programmer needs to be “force-fed” the state machine concept. The most important part of all of this debate, however, is understanding the state machine pattern. You have to understand the pattern first, and then you can figure out whether you need to spend the time in actually implementing it.

Thankfully, there are a few common red flags that indicate if this is the case:

A

stateor astatusattribute on any of your objects:Book::Order.first.statusInstance methods that return a

booleanvalue:Book::Order.first.shipped?Records that are only valid for a certain period of time:

User::Membership.first.subscriptions #=> "expired"

If your code base has any of these, you can probably benefit from a state machine. I went back and looked at my old web apps, and found that each and every one of them had at least one, if not more, of these situations. In fact, almost every Rails application is bound to have some variation of these three different scenarios, which means that we should all learn how to use state machines and become better developers!

So how do you actually go about creating a state machine? Well, that’s a whole other game blog post entirely. Tune in again next Tuesday, when I’ll explore how to actually go about implementing a state machine in your Rails application! Get excited! Like this:

tl;dr?

- State machines control the flow of events in a web application by using certain events to trigger different states or conditions.

- If you find that your app has methods like

stateorstatusandshipped?orreceived?, you should try using a state machine. - Still interested in the CS theory behind state machines? Check out these two super helpful blog posts on the subject here and here.